And so, at the risk of essentializing, will venture to say that Spirited Away is "so Japanese" (Tope, circa-all the time). It is difficult to sustain this reading at length and in all fronts, but it is also from this, I think, that any universalist framing can and should depart. To cite, in the laying out of the status quo that the narrative is set to (predictably) break, there is a detail that might escape a Western viewer (yes, we had become pagoda-worshipping Asia-centric hippies in that class). In the car on their way to the new house, ten-year-old Chihiro and her parents debate on the merits of moving to the new place. Chihiro, who is obviously a brat, is the least happy about the decision. She whines, holding some flowers: "My first bouquet - and it's spoiled."

And so, at the risk of essentializing, will venture to say that Spirited Away is "so Japanese" (Tope, circa-all the time). It is difficult to sustain this reading at length and in all fronts, but it is also from this, I think, that any universalist framing can and should depart. To cite, in the laying out of the status quo that the narrative is set to (predictably) break, there is a detail that might escape a Western viewer (yes, we had become pagoda-worshipping Asia-centric hippies in that class). In the car on their way to the new house, ten-year-old Chihiro and her parents debate on the merits of moving to the new place. Chihiro, who is obviously a brat, is the least happy about the decision. She whines, holding some flowers: "My first bouquet - and it's spoiled."Of course, the Japanese do not have the monopoly on making use of flora's (and nature's) ephemera to make a point. Here, we assume that the text comes from a strong Japanese sensibility and is therefore aware of these archetypes, these semiotic clues. Flowers are particularly resonant of Japanese aesthetics; ikebana is as concerned about the beauty of the arrangement as it is about the knowledge - the happy certainty - that such will not last, that it will eventually wither.

More ephemera: the abundance, the deluge of water in Spirited Away. The main enterprise in the middle of the adventure is a bathhouse, surrounded by a river. The train tracks that service it is beautifully submerged in shallow waters. Haku, Chihiro's first and staunchest ally, used to be a river spirit himself. "There's so much water it looks like the sea," Chihiro says at some point. Here we must remember that water, as an element, is as much an invocation of cleansing as it is of adaptability, of the need to change, of the change that occurs in Chihiro. Water: that which sculpts gorges and canyons over millenia, here witnesses and occasions the transformation in the ten-year-old.

And so it is here, in this constant ephemera (odd phase, surely?), in this liminal, elemental space where Chihiro's rite of passage takes place. The movie had been compared, both justly and unfairly, to other tales of "coming into one's own." Justly, for a portal clearly demarcates the passage; labor is rendered an utter necessity; and at one point, Chihiro is forced to forget her name as a means of giving up control (as if the point is not clear enough, Yubaba, the witch who runs the bathhouse, magically lifts off the text of Chihiro's name from parchment). But unfairly, for the similarities end there, and Spirited Away draws heavily on a culture that had seen the confluence - indeed the constant tug-of-war - of old and new, of paying homage to a dear heritage and needing to survive in a quick-changing world (Japan's post-war aesthetics and art movements all leaning on this ambivalence).

More: work seems to be a fundamental fixation that undergirds Chihiro's quest. On one hand, it is too easy to ascribe an anti-capitalist, anti-industrialist bent here; easy, too, for Japan's increasingly consumerist society to be dragged on to the picture. In fact, one of the first tests for Chihiro was serving a hulking stink spirit. Aside from another allusion to water and nature (and its degradation, which loops us back to Japan's post-war industrialist boom), this sequence alerts us to yet another fixation of Spirited Away: olfaction, the sense of smell.

The Japanese are no stranger to such attention. Kodo, or "the way of fragrance," is practically unheard of compared to ikebana and the tea ceremony. In the film, not only is Yubaba's nose extremely prominent, two of the film's most striking motiffs, food and memory, are closely linked with smell. Often admired for its stunning visuals, Spirited Away's narrative provokes much more than glitzy Hollywood animation because it invokes a sense that is often more visceral - be it pleasurable or agonizing - than sight. And so we recall that it was the aroma of food that attracted Chihiro's parents to the feast that would turn them into pigs. It was her ability - and willingness - to bath a stink spirit without covering her nose that earned her the respect of her colleagues.

As for hunger, explored in stunning complexity in Spirited Away, it elevates the film twofold: it is no longer just a Japanese opus and it is no longer just a movie for children.

Which leads us to: No-Face! This extremely needy spirit is one of the most brilliantly conceptualized and emotionally resonant characters in any feature I have ever seen, animated or otherwise. Lurking around the bathhouse for god knows how long, he gains entry when Chihiro, in a simple act of benevolence, lets him in. This act of kindness destroys him.

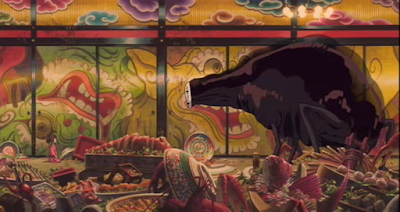

His desire awakened, No-Face follows Chihiro and offers her copious gifts, from bath tokens to gold. Denied of Chihiro's affection, he turns to others, first luring a frog-attendant with gold and swallowing him, before turning the whole bathhouse upside down by eating every food in the premises in exchange for gold. He becomes insatiable. He loves.

For what is love but a hunger, a desire to feast? In Spirited Away, there is a thin line between sustenance and destruction, between seeking completeness and enlarging the inherent void. If love is able to assuage hunger, where does it stop? The movie deems sincerity (Chihiro) more meaningful than ill-motivated quantity (the other attendants), but what of the supposed unconditionality of loving? Of the erasure of the self in the act? Was No-Face better off surveying such locus of hunger and desire as an outsider? Was I better off not meeting up with that 18-year-old nursing student in Seattle's Best SM Manila nine years ago, which had set off this horrible, horrible lovelorn-lovesick cycle? After all, Chihiro said, "something in here is making him (No-Face) crazy."

I don't know: clearly, no amount of poorly argued exposition can capture the journey of No-Face in this film, and so I will stop (plus, I'm getting emotional na, especially recalling that train ride when he travels with Chihiro to Zeniba's house, where all the passengers are profiles, shadows "on the verge of being erased," trudging on to unnamed, unimportant stations).

In the end, of course, everything is Japan (Tope, circa-all the time): the journey to a "new" world (possibly urban to rural), the inter-generation antagonism (the child knowing intuitively that it is an incursion), the primacy of roles (capitalist, gender, filial), the comment on nature and greed (cleansing for a price), the value of perseverance (Chihiro's stubbornness), and the double-edged sword of memory (recalling one's name as a means of salvation vis-a-vis an admonition to not look back and the submerged train tracks that, it is stressed, goes only in one direction).

If I have learned something from Spirited Away, it is this: that kindness transforms, and it doesn't matter how monstrous we've become; we only need to let it. Kindness is not the offer of entry or a feast, it is the ardent desire to partake in the humanity that Borges posits: in feeling that "we are all voices of the same poverty." Apologies to Dr. Tope if this is not "so Japanese." But maybe it is, because it is all.